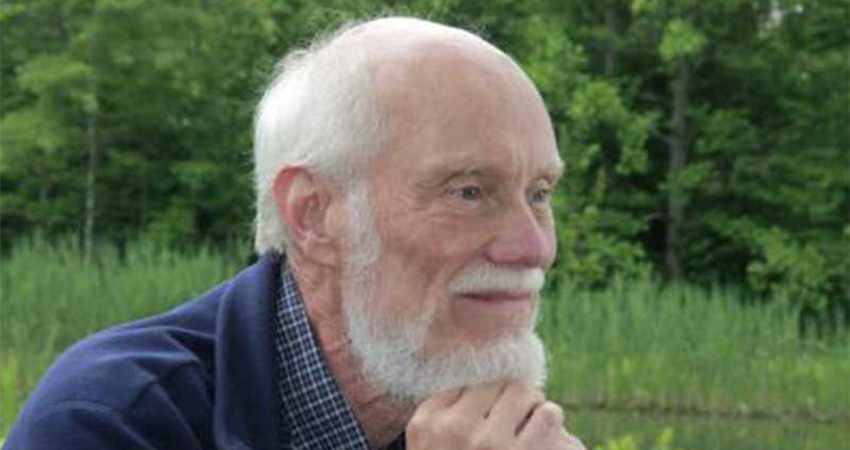

Nursing supervisor Owen Barron, RN, arrives at work just before 11 p.m., ready to shepherd residents in Noble’s medical levels through the night.

Night time at Noble has its own special rhythm, very different from the activity and sociability of the day. The quiet can be unsettling for some residents who can become fearful or unable to dispel upsetting thoughts or memories. For Owen there’s far more to a nurse’s job than dispensing medication. For him, holding a hand or simply spending time attending to a resident who’s having trouble sleeping is the core of what nursing is about.

But there’s more to this soft spoken, gentle man than an exceptional bedside manner. His youth, spent in a religious community, naturally had a profound impact on his character and outlook. Owen is a pacifist. And not a Johnny-come-lately pacifist, but born to it.

His English father and German mother were members of the Bruderhof, a Christian religious movement founded in Germany in 1920, whose tenets include the sharing of property and non-violence in all its permutations.

With Hitler’s rise, the Bruderhof fled to England in 1938. But as England prepared for war, the group found themselves unwelcome, their pacifist beliefs and the Germans among their members arousing suspicion. So the community moved once again, this time to far off Paraguay, which welcomed Europeans and had no requirement for military service. Owen was born and grew up in Paraguay until 1960 when his family were among 200 Bruderhof who returned to England. Four years later they came to Connecticut to join the Bruderhof community in Norfolk. (The Norfolk community closed in 1997 and its members moved to other Bruderhof communities.)

With a natural facility for math and physics, Owen studied electrical engineering at a two-year technical school, intending to continue his education and become either a doctor or a teacher. But by the mid-‘60s,Viet Nam and the draft turned many young men’s plans on their heads. Despite being a British subject, not a U.S. citizen, Owen was subject to the draft. Firm in his life-long beliefs, he applied for conscientious objector status, which his local draft board flatly denied. A second hearing had the same result.

Senior members of the Bruderhof appealed on his behalf directly to General Lewis B. Hershey, Director of the Selective Service System. General Hershey was responsible for inducting a prescribed number of draftees into the armed forces on an ongoing basis, yet he was sensitive to the concept of religious freedom and believed that religious minorities deserved protection. He had developed an alternative service program for conscientious objectors, assigning them to jobs where they could serve the community rather than serving in the military. General Hershey personally approved Owen’s CO status and he began his two-year hitch working as an orderly at New Britain General Hospital (now the Hospital of Central Connecticut).

Owen liked the hospital atmosphere and the people he worked with and stayed on for an additional year after his alternative service requirement had been fulfilled. Seeing up close the work that nurses did, he realized that he didn’t have to become a doctor, but could find much of the same satisfaction he was seeking as a nurse. He enrolled in New Britain General’s nursing program and emerged as an RN three years later.

After a head-clearing hike of the Appalachian Trail, Owen headed to Los Angeles, joining the nursing staff at Cedars Sinai Medical Center, working in the ICU and neurosurgery unit as well as the Deluxe Unit, reserved for the rich and famous. But California was really just the staging ground for a far more exciting adventure. Owen was set on gaining a job as a public health nurse in Alaska, flying with a bush pilot to treat patients in the most remote and precarious locations.

While waiting on Kodiak Island for his nursing credentials to be approved, Owen had time on his hands. He frequently found himself drawn to the docks, fascinated by the life of the fishermen heading out into the Gulf of Alaska. Deciding he’d rather take to the sea than to the air, he signed on to a crab fishing boat. For two years he worked twenty and more miles out to sea for a month at a time. It was dangerous work and more than once his boat nearly capsized. But the real danger waited on land.

Back in port, he was driving a truck filled with crab pots late on a cold and wet night. Suddenly another truck was heading straight toward him and they collided head on. The driver in the other truck escaped unharmed, though his passenger was killed. Owen was unconscious for hours, and when he awoke his mind was racing and he was beset by unsettling thoughts and dreams of the accident that persisted for weeks.

As he recuperated Owen became more spiritual and after much reflection, study and talking to others he reached a larger, more comprehensive view of the world and his place in it. The process took months, but it was a life-altering period and in many ways made him the person he is today.

Back in Connecticut in 1984, Owen saw a help wanted ad for a night supervisor at Noble Horizons. He applied, thinking he might do it for six months or so. Working at Noble proved to be much more rewarding than he expected, however, and he came to feel that it was a calling, how he was meant to serve humanity.

In addition to finding work he enjoyed, Owen met his future wife, Jocelyne, whom he describes as “the universe’s way of keeping me here.” Raising four boys on her own, she worked nights as a CNA to be available to her children during the day. They were married in Noble’s chapel in 1987, with many of the residents they cared for as their guests. One of things that happens in long-term care is that residents and staff often become very close, so naturally those residents wanted to be there when two of their friends were married.

Owen took on the role of being a father to Jocelyne’s sons with the same sense of commitment that he has brought to other aspects of his life. “It’s an amazing way of being with people.”